I’m off the grid today, and all day tomorrow. My blogging is compromised a bit, but something is better than nothing.

As most of you know by now, I’m participating in Tayari’s WriteLikeCrazy challenge. My goal was to write a minimum of 15 minutes a day toward a goal of 4 hours a week. I also wanted to publish one blog per week. Those may seem to be low goals, but for someone who wasn’t even approaching those numbers, it was a stretch. My underlying goal was to build a writing habit.

Almost at the same time, Aliya invited us to participate in the 30in30 blog challenge, with the goal of writing one blog a day for 30 days. Talk about kicking it up a notch! I decided to do it because the thought of it made me uncomfortable and I’ve been striving to push past my perceived limitations.

Sidebar: that’s also the reason I lift weights – to steadily and tangibly increase what I’m able to accomplish.

As I’ve mentioned before, the daily commitment to publish something has made me prioritize writing in a way I never have. It’s the reason I’m spending my “free time” writing.

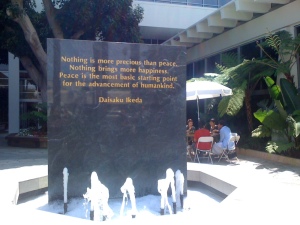

I’m at a Buddhist study conference and it’s an all day, all weekend affair. Two-hundred SGI members from North America and Oceania are present including people from the continental United States and Hawaii, Canada, New Zealand, one brave woman representing Barbados, and another representing Palau.

We’ve gathered to learn more deeply about the theory of Nichiren Buddhism and how to apply it in practical ways to improve our lives and society at large. Indeed, at the root of our work is the development of a peaceful society – something not too far afield from a caring community.